Jade, cool and hard to touch, yet gracefully beautiful and tenderly warm to look at, is the most constant element that withstands time and a culturally rich object that more than anything else holds the deep feeling and profound thinking of the Chinese people.

As far back as over seven thousand years ago, our forebears had learned from the toil of life such as digging and logging that "jade" was a stone of beauty and eternity. With a glistening sheen just like the springtime sunshine, believed to be high in jingqi (vital force or energy), this beautiful jade was fashioned after the concept of yang and yin into round bi discs and square cong tubes, and marked with deistic and ancestral images as well as "encoded" symbols. A power of "affinity" born of "artifacts imitating nature", so they hoped, would enable dialogues with the Supreme God, who imparted life through mythical divine creatures and thus created humans. Out of this early animistic belief, came the unique Dragon-and-Phoenix culture of China.

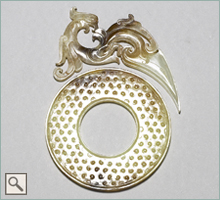

Humanism arrived with passage of time and social development. Gradually dissociated from animistic properties, jade ornaments in the shapes of dragon, phoenix, tiger, and eagle, originally symbolic of clan-families' spiritual gift, or innate virtue, took on new interpretations as Confucian gentlemen's virtues: benevolence, rectitude, wisdom, courage, and integrity.

During the Six Dynasties and the Sui-Tang era consecutive waves of foreign influences arrived and impacted the Chinese jade art significantly. Free from either spiritual or Confucian undertones of jade, newly formed literati class in the Song and Yuan dynasties was keen on both nature and humanity; their art was in quest of realism and ultimate truth. Along with realism, however, archaism existed in support of political orthodoxy, popularizing antiquarian styles for jades. Jade carving exemplified the quintessence of the Song and Yuan culture.

Arts and crafts developed into an age of sophistication in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Starting in the mid-Ming, the region south of the Yangzi River enjoyed great economic prosperity; jade carvings became ever finer and more elegant under the patronage of literati and rich merchants. In the 2nd half of the 18th century, the conquest of the Uygur region of Eastern Turkistan further gave the Qing court direct access to and control of the Khotan nephrite mines; jadeite also started to come in from Myanmar with the active development by Qing in the southwestern region. Driven by the imperial house's taste, jade carving experienced an unprecedented thriving period.

Throughout the nearly eight-millennium development, jade carvings have first embodied the Chinese ethic of religion that was in awe of heaven and in reverence of ancestors. Then art in pursuit of realism in both form and spirit peaked after the medieval China, manifesting the academic heritage of Chinese scholars in seeking the intrinsic nature of things. The two concepts jointly attest to our national character as well as the deepest and most profound connotation of the ancient Chinese jades, the art in quest of heaven and truth.