Jade the mineral is hard and tough. Both nephrite and jadeite range between 5.5 and 7 on the mineralogical scale of hardness. The fibrous monocrystalline structure renders extreme toughness, making nephrite one of the toughest minerals. Even tools of copper alloys or iron, cast and made once people learned how to smelt metal, could not cut and grind this tough material. Therefore since the very beginning nephrite has been universally carved with a method called "using stone to grit and groom jade".

Finely grounded minerals harder than jade, such as quartz, garnet, corundum, or diamond, are used as abrasives in combination with tools of wood, bamboo, stone, bone, and linen, as well as of copper, iron and steel, to cut the jade material and to shape it into forms. The abrasives need to be prepared first by pounding and pulverizing various sizes of stones and grains of sand, then graded into groups and steeped in water for ready use.

The procedure now and past, in rendering products fine or coarse, invariably involves the following steps: cutting open the material, boring holes, shaping into forms, and carving patterns. Regardless of the particular shapes and textures of the tools used, either when the straight blade is slicing back and forth, or the round blade of the cutting wheel spinning in high speed, or the solid or tube drill pressing down in rotations, or the string tool pulling to and fro, a slurry of moist abrasives is constantly added to help the tools in abrading the harder substance against the surface of the jade material. The hard and tough jade can only be cut, shaped, and scraped this way. Except in the final polishing, water is always indispensable so as to lower the high heat produced by friction, to reduce the wear of the tools, and to prevent the jade material from cracking or exploding.

The many millennia-old tradition of Chinese jade carving have developed techniques featuring primitive simplicity or elaborate sophistication. There are raw materials and semi-finished works in our collection, as well as many finished carvings with clear marks of manufacture left at the backs, bottoms, or some less conspicuous spots. All these provide important clues for understanding the tools and procedures used in creating these beautiful jade artifacts.

Cutting Open and Shaping

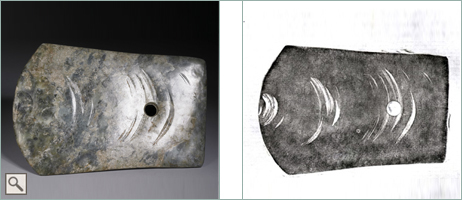

| Jade Yue Axe Late Songze Culture to early Liangzhu Culture c.3500-2900 B.C.E. |

Marks left from thread cutting |

Drilling Techniques: Ting Bores

| Jade Pei Pendant with a toothed beast mask pattern Late Hongshan Culture c. 3500-3000 B.C.E. |

Stick drilling marks left in the wall of the drilled holes |

Drilling Techniques: Tube Bores

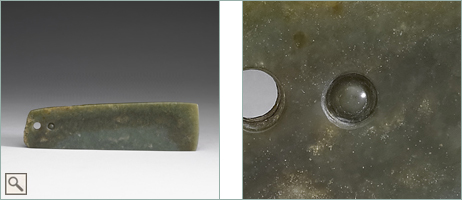

| Jade Shovel Longshan-Qijia System c. 2500-1700 B.C. E. L. 15.43 cm W. 4.4 cm |

An abandoned pipe drilling hole, leaving behind a pointed jade core |

Drilling and Piercing

| Huang Ornament with openwork pattern Liangzhu Culture c. 3200-2200 B.C.E. L. 8.54 cm |

The round hole was drilled first, and the filigree patterns are then made with a thread cutter |

Carving Patterns

| Jade Ornament with toothed animal-mask pattern Late Hongshan Culture c. 3500-3000 B.C.E. L. 19.1cm H. 6.9 cm D. 0.2~0.35 cm |

Resulting in rows of depressed, concave lines |

From Design to Finish

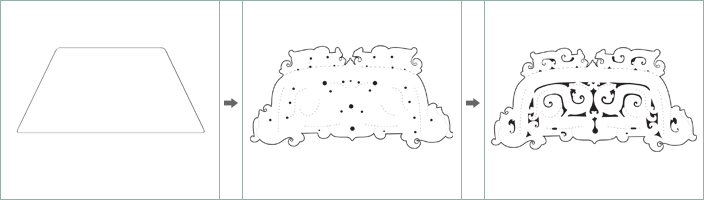

| a. First cut open and shape into an approximate trapeziform | b. Follow the design to carve out intermittent

engraved lines for alignment "nail marks and bore out holes", using small tuo wheels |

c. Next pierce out and through the patterns using metal wires with jieyusha abrasives |